The ambivalent ones

I was looking at her, dubious on whether or not to ask that question. Not that I had prepared for that, but here she was and I intended to connect with her, I didn’t want to upset her in any way. Perhaps because she strangely reminded me of my grandmother, although she had not much in common with her; my grandmother was witty, concerned, and discreet, whilst Rosa was loud, cheerful, domineering.

I was letting Rosa show me around, particularly that wall where she kept all the photos of relatives. A mix between a hall of fame and a hall of death. Given her age, a lot of relatives were in fact dead, back home as here in Australia. Their pictures were hanging on that wall, longing to be remembered, or for another shot at telling their stories. Some other pictures, those of nephews, nieces and children were quickly growing out of their own skin already.

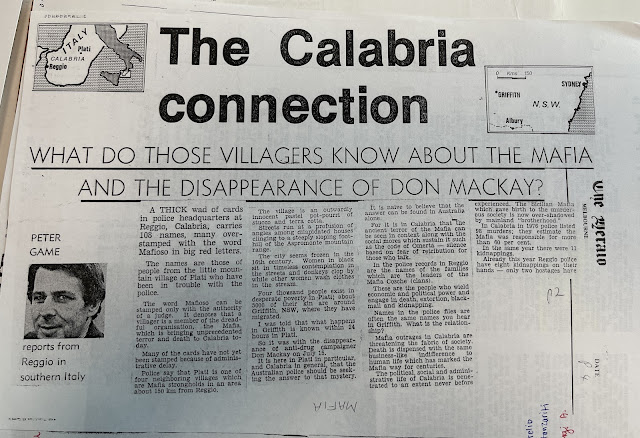

I was staring at them, and kept wondering: would my grandma have done that, if she were here, and not back home, in Calabria? Would she have a wall of fame and death? There could have been, on that wall, the picture of her, my grandmother, in between the other family members that the village had lost to stubbornness, folly and a good dosage of desperation, through the migrant journey.

Rosa showed me around, she smiled a brilliant smile. Her voice, notwithstanding her old age, was firm and clear, her strong tone is still unforgettable. She spoke about her brothers and sisters, about the long trip to Australia, about the reasons why her father had decided to travel so far away. She spoke about her missing shoes, and the arrival down under barefoot. A new land, barefoot. Quite an image of rebirth.

That question was swirling in my head, as I was approaching the table where she had prepared food and drinks. I could have easily stepped into a Time Machine without realising: back to the nineties and to my grandmother’s living room. Where she was always preparing some food and drinks, just in case someone arrived unannounced. I swear there were the same chairs, the same table, perhaps the same utensils? I didn’t know anymore, but I felt her, grandma, as I often do, when I am uncertain of something that relates to the Mountain. Her voice in my head, my own personal Madonna, warning me “Anna, do not forget everyone learns how to hide their personal inferno”.

That question, simple and trenchant: did *you* know, about him? How much did you know about him?

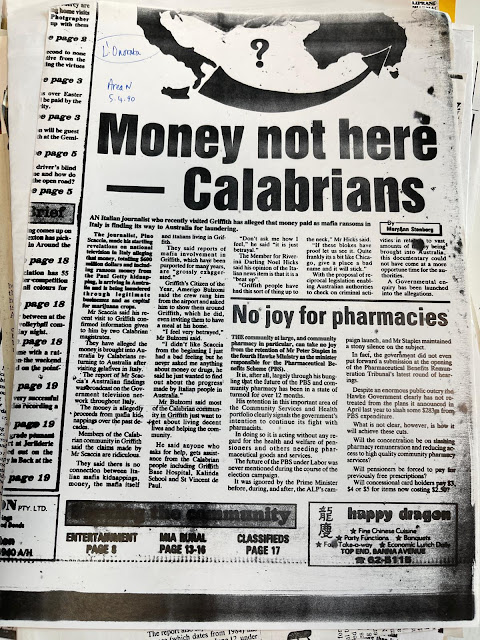

Him. A boss, a mafia man, a key person in the honoured society, in the ‘ndrangheta. He was someone who - it was said - had killed. Someone who - it was said- had made money through drugs, extortion, violence. Someone who - it was said - had accepted money from the kidnappings back in Calabria and used it to his own advantage. Him, Rosa’s brother, whose funeral card was on that hall of fame and death, with a touching phrase that said something like “you lived with kindness, you died in peace”. But was it peace? Was there kindness?

I bet I knew the answer to my question for Rosa, a question I could not bring myself to ask. She both knew and didn’t know. There was not much to know. All you needed to know was what you saw. There was racism and discrimination. There was a lot of confusion: of intent and intention; the stories were simplistic; the attacks by media were relentless; the misunderstandings were the only things that was hitting the headlines. He, he was a good man, in the everyday. A faithful and caring husband, father, brother, uncle. He was stubborn and a natural-born leader: he could ice someone out with his eyes, but those eyes were also warm and in them you could see both the mountains and the sea of Calabria, as deep as they were.

And yet, and but… there were at least some of the crimes, right? There was at least some of the harm, correct? Was there perhaps also the manipulation? It is difficult to imagine Rosa being manipulated, her candour and simplicity, genuine traits of a woman from the Mountain. Unless… unless, it wasn’t proper manipulation, as much as it was accepting the ambivalence.

The ambiguity of him, led to the ambiguity of her. To a radical uncertainty of the value to give to experience, and to him.

Could he be both the gentle man she remembers and the mafia boss many feared? Could his peace be the ambiguity and ambivalence?

If I had asked my question - did *you* know, about him? How much did you know about him? - there was going to be a follow up question: did his story touch you? Did it harm you? Did you even understand that harm?

Could Rosa’s peace, her attitude, her domineering cheerfulness be in the acceptance of that ambiguity and ambivalence about him - being fine with it?

Could you accept to live with some degree of ambivalence about someone you love, because the ambiguity surrounding them is too radical and no amount of evidence could ever resolve it?

.jpeg)

If most people said one thing about him, with evidence, proof, logics and Rosa knew- in her heart - that she trusted another version of the truth, how was she ever be able to survive for so long - her whole life! - in the marginality of her own version of that story? Was her own judgement enough not to be harmed by the stories, the media attention, the narratives of the papers, the claims of the neighbours, the judicial trials or the inquiries, the pointing of fingers, the rolling eyes? How did she do it, without accepting a certain degree of pain with it.

Did Rosa know she might have been a victim, even when the whole of Australia considered her complicit?

And was Rosa ever able to differentiate between discrimination and a mafia accusation, if she knew - she felt on her own skin because of her surname and family bond - that the latter comes with the former and the former comes with the latter?

Was she ever able to accept any version of the story about him that came with wrongdoing and wickedness, when she didn’t see any in him? Was she ever taught how to see, to look for that?

There is, of course, a difference, between the perceptions and the reality, the narratives and the facts. And yet the life we live, when perceptions and narratives are ambivalent because reality and facts are ambiguous, is as real as the one we choose not to live.

Rosa was showing me the drawings one of her nieces made for her, a drawing about a region, Calabria, the little girl had never visited but she already loved as that’s where grandma Rosa is from. Rosa’s eyes were lucid, matching the emotions that made her hands tremble a bit, as she knew, perhaps, the little girl will one day ask, with her perfect Aussie accent, about him and she will have to give her an ambivalent choice to make.

How hard could it be, for Rosa, to pick a side and still trust herself? How hard could it be for Rosa to see herself as a victim, whilst she was robbed of the possibility to attribute free-of-judgement value to what she valued the most?

-------------

I really feel for Rosa here. Indeed is she a victim? Is there a way for a victim that doesn't know to be a victim to be actually considered a victim?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment. If you are asking yourself that question does it mean you consider her a victim? And it is a great question, can victims be considered as such without their knowledge. Theoretically yes, but practically things change. Maybe one of the problems is that we associate victimhood to fragility, which might not be case always....

DeleteVery cool

ReplyDeleteThank you! Tell me why! ;)

Delete