"You are Calabrese, now apologise!": learning about yourself and the "onorata" in Australia (part one)

Dear you,

yes, you. I want to talk to you about the honoured society. Have you heard about it? Are you and your family "in" it? Are you "it"?

What I know about you is a lot. You grew up in a rural area in New South Wales, but there was never a less "Aussie" boy than you. Even if you wanted to be, you couldn't be.

You were Italian, you were Calabrian, and you could not forget it at any stage of your growing up.

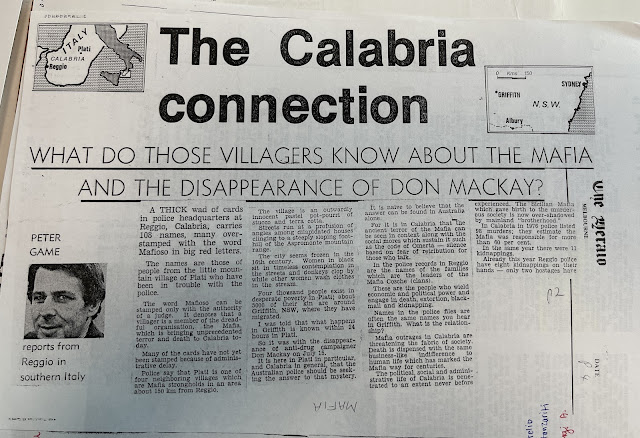

Your mum and dad had arrived on a ship a while back, they are from a small village in the Aspromonte. They came here with other 50 or so people from the same village.

You know them all, as for most of your life you all lived in the same streets, one near the other, a duplication of the village back home. You spoke the dialect with the elders, you went to the funerals, you saw all their photos from "home", the houses they had left behind, their relatives' children, their ancestors.

You played with their children and also with them and also used the language - both a barrier and an opportunity - a barrier for outsiders, an opportunity for identity-building.

Growing up, English became your new mother tongue, and you couldn't wrap your head around the fact that your parents still could not properly speak it. Your Australian friends - once you managed to make some - made fun of your folks, yet they loved coming to your house to taste your mum's merenda.

You were a wog, whether they said it to your face or not, you were one, you even behaved like one. After all, growing up it was comforting to have a pre-construed identity right there for you to use. You acted catholic, for once. You tried, you pretended to be, you had to go to mass when you were little, you went to a catholic school, like all the Italians, and you had to do the whole rituality of it, baptism, communion, confirmation. It never mattered really, but even today when you feel like cursing, Gesù Cristo or La Madonna, you feel ashamed and you hear your grandmother shouting: "You are Calabrese, now apologise!".

Linking forever being Calabrian, and being ashamed, for you. It wasn't really intended like that but then again, your childish mind and the firm voice of your grandma were quite a lethal mix. You are Calabrese, now apologise, meant you had to apologise for being Calabrian, somehow. Sorry, for your mum misspelling this or that word. Sorry, for your cousins coming over from the motherland and looking cringe. Sorry, for your father being illiterate. Sorry, because in summer your olive skin would get darker and darker and you didn't look Australian.

The weirder part of all of this was that you didn't know who to apologise to. And so, your initially imprecise audience, became wider and wider until you were already an adult and you realised that you will forever feel somewhat in need to apologise and that makes you mad.

Inferior and ashamed as they made you feel, you chose to rise above, cause they don't know you feel actually superior. For all your life you watched your father and your mother coming from nothing and surviving no matter the shame. And you are proud. Proud to be Calabrian - even if you are not just Calabrian, but that doesn't matter. You grow up and you can choose, where your identity aligns.

You think that Australians don't know how a true Calabrese survives: keep your head down, work hard, be loyal, don't trust anyone but family, fatti furbo - wise up - be cunning or they'll see right through you. Don't show too much of your intentions, but always be polite, always be respectful, always have a faccia pulita, a clean face.

When you were a child, you had to be ready to apologise, apologise, apologise, as a good Calabrian knows how to behave. But as an adult, and as a Calabrian man, you don't apologise, they have to apologise to you.

Why would you apologise, when it's for you - and not them - that something has always been missing?

You were supposed to grow up elsewhere and be among people like you, and yet here you are, the different one, a wog. You felt almost illegitimate all your life. Just because your parents moved and you, you had to endure their choices. They said they did it for you and your siblings, but really you wonder what would you have been back home, all the time. If it was so great at home as they say, why did they leave anyway. You see your doppelgänger - the other you who could have been, back home, in Calabria - and you try to live up to his expectations of you.

You were supposed to get to know the villages that your parents and all the other village folks talk about, know the stories, know the people, know the reason why the 'ngiuria, the nickname, for each family came about. Why is Zu Frank called u Jancu, why is zu Luca called u Versu?

And more importantly, among the traditional singing to the Madonna, and the cooking of grandma, and all the rules of behaviours you religiously followed all your life, just like it would have been if you were home, why is l'onorata the only thing you thought would protect you all?

They taught you that structure and discipline only work when there is respect. A man without respect is invisible, and being invisible accelerates death and the fear of death.

They taught you that respect is honour and honour is worth fighting for. For honour, even revenge is justified, as a dead man wanders the earth if he dies dishonoured. Honour is the only thing that does not cost money, it's the treasure of the poor and the rich alike. This they have taught you. That if a poor man is honourable, then he will be respected as the king.

They have taught you that you are Calabrese, and you know how to apologise if you need to. But to those who made you feel inferior, they'll know your blood is your strength. Your blood makes you a man. Your blood contains traditions and rituals and strength you can't even imagine.

They have taught you that you can defend yourself, and that your honoured society is as old as honour. They taught that people don't know anything about you and will try and undermine your identity at every turn; they won't understand how you feel when you are part of this, when you are protected by it, when everything else is far and untouchable and unreachable but this, this is here and close and makes you feel like a true version of yourself.

They have taught you that you are Calabrese and Calabrians don't take orders from anyone, but their own kind.

And now that you are an adult all you want is to connect the dots. You look in the mirror, your doppelgänger of the life you didn't have, has come out and talked to you about a land you felt you always knew in a language you have always spoken.

You are still a wog, but you are in control.

Dear you,

yes you. Are you in control?

(Continues...)

---

Copyright text and photos (New South Wales) Anna Sergi

This text is not about anyone in particular, but is inspired by two different men.

And you reader, does any of this made an impact? Feel free, as always, to comment, even anonymously (and politely, if so!) below!

This is so true and relatable,even outside the ndrangheta universe. The feelings of estrangement and uncertainty shared by many migrants' children, and in the microcosm you describe the strong connection offered by the " honoured society", his rules and language and so on. You are offering a unique and fascinating point of view, thank you.

ReplyDeleteDear Francesca, thank you for picking up on my intention. To make this “monster” everyone describes as such, the ‘ndrangheta, more relatable, not as a justification, but as a humanisation of its drives and its social implications and origins. Humanising processes (not just choices) through social analysis should help us understand it before any condemnation. I have heard so many stories by migrants in Australia and those stories are all part of a bigger picture where also ndrangheta families existed and exist, and I want to try and capture that. Thanks for reading thanks for commenting so positively and engaging so meaningfully.

DeleteYour research and written pieces continue to evoke strong emotions within me. Your words carry a profound weight and seem to be rooted in the values, culture, and traditions of our families, and yet I can't quite put my finger on it, it mostly feels like I need to explore my own self through these words too somehow, not sure how. These posts talk about us.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your feedback. I am glad this is making an impact and I hope it doesn't hurt. The intent is, as always, to bring to light things that are not always pleasant to talk about but necessary for identity-building as Calabrians.

DeleteI’ve had to read this several times, and each time it’s brought up a different thought or feeling.

ReplyDeleteThis is the kind of writing I love from you, a bit more free flowing and evocative, like much of Chasing the Mafia reads. Don’t get me wrong, I read your academic pieces voraciously, but you’re doing something different here and I’m here for it.

Thanks so much Steve, honestly I prefer this type of writing too! Of course I have to balance the two also because it's not always easy to argue that also this writing is underpinned by the academic research of the rest. It's a learning curve for me but I am so glad it is striking a chord! Any suggestion for topics always welcome!

DeleteWell written Anna. I grew up amongst many Italian families in rural South Australia. We had lots of fun and of course there was lots of 'banter' going between us. My friends parents barely spoke a word of english but we still communicated especially when there was food involved. In recent years my friends confided in me how hurtful the name calling was. Wog, wop, etc. When they were young they would laugh it off but inside they were hurting. We all must be kind and thoughtful with the words we use - even in jest. Keep it up Anna.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing that and I am sorry about the name calling and the hurting involved but I am sure the good memories trump the hurtful feelings, or so I hope. I am glad that I managed to convey something that even partially described lived reality. The way this type of silent hurting works underneath, not for everyone of course, is something that we must acknowledge when we judge people's choices later on. Thanks for reading!

ReplyDeleteOkay, this comment has been a while coming. I really struggled with what I took to be the message of this one..? Perhaps it’s because I am not, in fact, Calabrese; my forebears hailed from Spain. But the migrant experience, to an extent, is the same for most in Australia.

ReplyDeleteBut I mean; isn’t it our own responsibility to forge our way? I see my uncle doing it his dodgy way. I could’ve continued that tradition. But I had a choice. I had a hand in deciding my own direction in life. It feels disingenuous to me for a person to point at some form of ethnic guilt or post-migrant identity crisis in 2024 Australia as reason enough to break the social contract and adhere to criminality. Even 2004 Australia, we had a choice. So did all our cousins, and friends, and extended friend and family groups throughout our local Spanish* Clubs (insert Greek, Polish, Macedonian, Cypriot, Italian or whatever here), those bastions of culture scattered throughout our industrial estates and suburbs. They are the holders of knowledge in the culture: our abuelos, our nonnos, our opas etc.

Perhaps I’m simply missing a deeper meaning to understanding here. I’ve come back to this post several times and typed up a reply, only to delete it for fear I haven’t managed to articulate what I’ve wished. But man, this one stirred up some things in me Anna. I’m still not sure my point is even coherent. 🙃

Very coherent! I don't think you are missing the point, perhaps you are looking for a different point beyond what I am making here. The point here is to describe how self perception gets its own shape within the cultural milieu of origin; of course there is free choice, but to some extent free choice is never free of our cultural and social conditioning. So, if someone, like this man here, looks at himself and feels the way he is can be justified (neutralised even) with a cultural reference and throwback, then this is still his own free will. All I am trying to do is to say what makes the "Calabrianness" as it was or is taught to people; what you do with this CAlabrianness - and how it is taught (like a religion or like a component of identity?) matters for what you perceive yourself to be.

DeleteAh. See I knew that if i dug a little into your piece I’d get a response that helps me understand in a different way.

DeleteI appreciate the subjectiveness of this almost gonzo-style approach to content informed by your field work..it’s such a unique lens. There’s obviously something to be said for the “Calabrianess” of an individual. That’s a social stigma not all South West European cultures encounter, admittedly.

Thank you! Every culture has this I think but when there is an organised manipulation of culture, like in the case of the ‘ndrangheta, then the only way for me to understand this manipulation is to explore and unpack the culture its make beliefs its values and their torsions. Hence why different forms of communication are helpful to me!

DeleteThe noun or the verb?

DeleteThanks for your work, Anna. This article remembers me of my personal background as a migrants' son, even though just from Southern to Northern Italy. My schoolmates used to joke at me for my pronunciation as a kid; there was complete mistrust in everything but family; and this feeling not to belong to the places I spent all of my life in, not to belong to any place indeed. If I think of it now, even if I was born and raised in Milan, at 44 I recognize that the greatest part of my friends have always been of Southern Italy origins or born there; really integrating beyond formality proved to be difficult. I'm writing this to confirm your assumptions: in Australia it must have been a lot worse. I'll keep on following you.

ReplyDelete